For anyone living in London the cost of housing is a hot topic. The price of housing has been rising faster than income for years. Initially effecting students and the low wage earners, expanding to the professional middle classes. The housing crisis seems to be a relentless chronic condition of the city. Year from year on the cost of a home in London rises 7% per year, or 6.5% above inflation. UK house prices are the second highest in the world per square meter, just behind Monaco. Everyone from service industry employees to corporative professionals are being priced out of the city, as housing in London has simply become unaffordable for most ordinary people. This upheaval has now started to effect the commercial side of the market with office space disappearing into housing conversions with the consequential office price inflation.

The housing crisis is one of the top political talking points in England, but most appear to be identifying conditions rather than causes as the underlying reason for the crisis. The British planning system has a significantly adverse effect on the economy yet very little is being done to solve it.

The reason for the crisis is simple a matter of supply and demand. The lack of construction of new housing is driving up house prices. The reason for this lack of supply is not the unwillingness of developers to build, but the planning system and its inability to accommodate progress. With supply being off kilter for so many years, house prices are now growing in double figures in places.

This price inflation offers a great incentive for new and existing residential units to become international “investment” rather than homes. This kind of investment profits makes the actual use of these investment residential spaces impractical and units are treated much like other investment commodity locked away rather than used. This skews the growth of the build environment further with new “million pound” homes being kept empty and not contributing in any way to the housing need. The investment is not a cause, but a condition of the crisis.

The British planning system is not a proactive system but a reactive one. I.e. it does not plan or implement the future progress of the built environment as it’s name implies. The existing build environment is the Master-“plan” with any new development treated as a proposed change to the master-plan. The same rules apply to anything from extensions of existing properties to large scale developments. A reactive planning is quite exceptional amongst western planning systems as it is unable to plan for the future and has little ability to react to given situation.

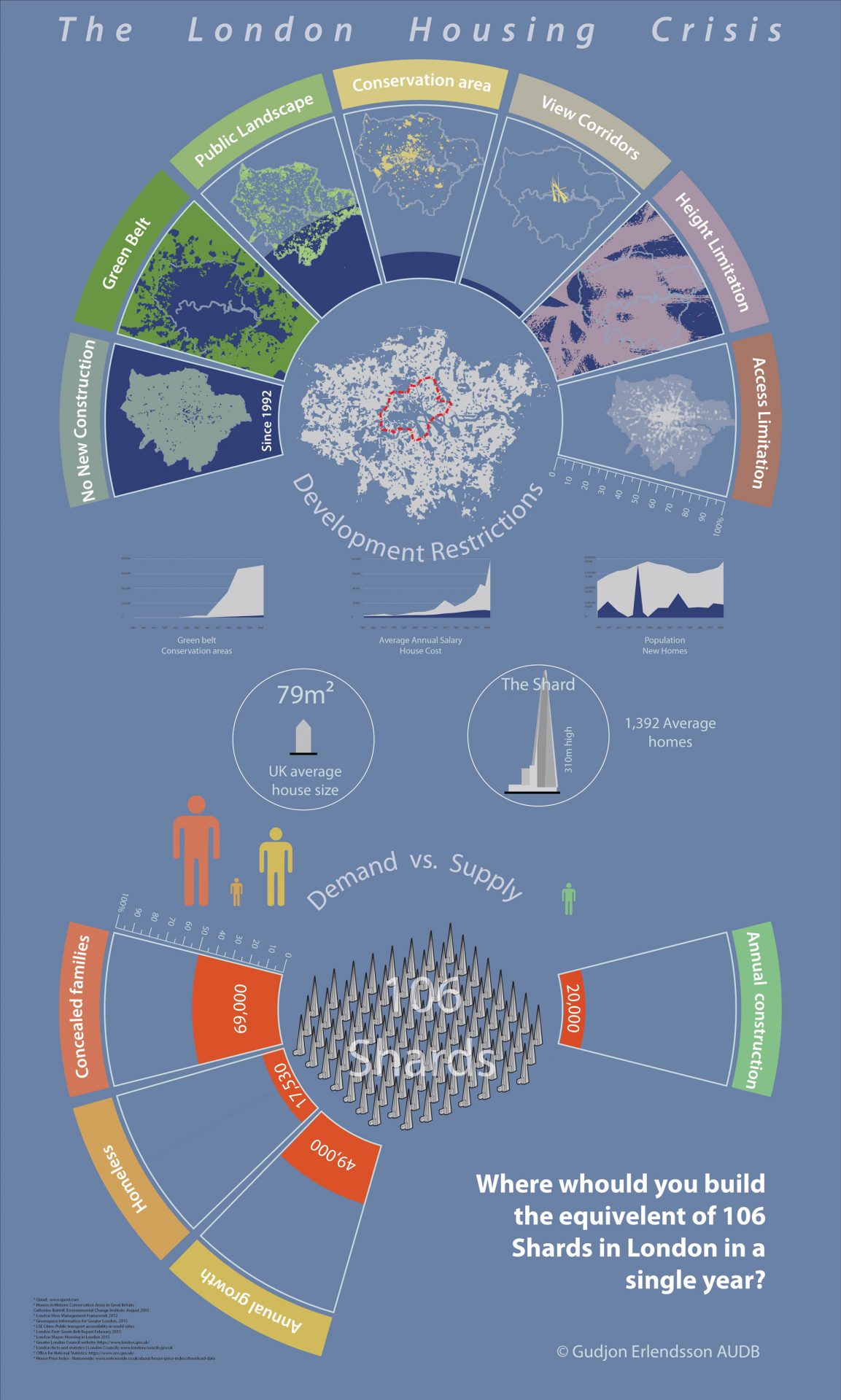

It’s human nature not to like change, as change is often for the worse and it’s better not to gamble on it. Existing residents consequently do not like new development or changes in their environment, and will elect politicians that are equally against it. A reactive system therefore creates a rift between the wider need for future growth and the local demand for status quo. With all responsibility for growth in the hands of private and commercial developers versus planning officials and residents as the guardians of the status quo. London planning is operated through multiple and growing restrictions against development.

Where London can not grow:

NOT OUT

The city grew exponentially into suburbs between the wars, with the 1930s showing the biggest building boom in the cities history, primarily in the suburbs.

After the war this led to a movement calling for the restrictions of the cities outward growth and a development of a Green Belt, a wide territory of building limitation around the city. The Greenbelt has grown since the 1950s with the growth only slowing in the last 20 years.

NOT IN

Renewal and optimisation of the existing built environment is naturally restricted by a reactive planning system. Any changes are restricted by consultation with local residents and interest groups, conservation area restrictions, listed buildings, sunlight and daylight constraints apart from the personal interests and abilities of the bureaucracy. and simple. In many cases NIMBYism (Not In My Back Yard) is the focus of local councillors who are elected by local residents with no interest in change. The young, the non-local and others in need of housing have no representation on the local level. Meaning that most of those involved in the planning process, from the Conservation Officer, neighbours to Councillors are interested and committed either to the past or stagnation. Not a single representative of progress or ambition is represented in the process apart from the party making each proposal.

London is one of the greenest cities in Europe with local access to green spaces from every household in the city. Including large swaths of parkland. These are qualitative amenities that do impact development, with restrictions on new built close to those amenities.

Conservation areas and listed buildings are growing in number and size. The structure of the planning system, putting Conservation at it’s core, means that these put severe limitations on new development and the refurbishment of the existing fabric. UK has the oldest, and the least sustainable built environment in the whole of the EU . Anyone working in the building industry experiences conservation’s extended power, as the same restrictions are often placed on new development proposals close to listed buildings and conservation areas. Close can mean up to a kilometre away in some cases. With 70% of some central brought listed as conservation areas, the city is turning into a museum of pre 1920s architecture.

NOT UP

London is surrounded by airports with flightpaths criss crossing the city. This puts a practical restriction on any high-rise building in the city. The Shard is the tallest building in London and is the maximum height any building is allowed to rise at 330 meters.

Since 2004 the city has started implementing restrictions on tall buildings in the centre of the city using a planning tool called“view” corridors. This is another tool focused on restricting development in the centre of the city.

NOT DOWN

With the natural development of the city restricted and the resultant price increase, people are being forced to undertake subterranean extensions to their homes rather than move. These kind of extensions started in the more affluent areas of the city, such as Kensington and Chelsea, but have now spread out into other areas as restrictions on new developments put pressure on finding alternative solutions. As expected councils are now either restricting or banning basement constructions in their areas. Basement excavations are expensive and limited in scope, and unlikely to properly solve the crisis created by consecutive governments for the 21st century London.

DICKENSIAN solutions

None of the planning policies are able to restrict population growth. The 21st century is the century of the city, with people relocating to major cities for economical and cultural reasons. The last time this happened in London was at the time of the 1st and 2nd industrial revolutions in the 19th century. The results in planing terms were twofold. The development of unplanned slum building and the division of existing homes into smaller and smaller residences. Whole or even multiple families living in a single room was the norm. 21st century London is not place of unrestricted construction, due mainly to property ownership and building control, although new buildings in the UK are 40% smaller than in cities of similar density. So development now follows the second of the Dickensian housing development with increasing division of large and medium sized homes into smaller dwellings.

Where we are going?

To local residents all of these restrictions appear to function in order create or protect free amenities. In fact these amenities are anything but free. The cost is simply diverted from residents to those who do not already own their home, the under privileged, young people and anyone renting or purchasing a property in the city. Conservation, green areas, view corridors and other planning restrictions are effectively paid for by first time buyers; a privatised “tax” at several times their annual salary.

Any leadership training teaches that indecision and inactivity has just as much impact as any good or bad decision. The planning system and its associated planning restrictions are causing ripple effects of problems. One is the division of homes and the increased of dwellings of multiple occupancy. With middle aged, middle class people living in shared households a lifestyle previously restricted to university students. Another is the exodus of people out of London seeking affordable housing, while commuting into the city. The greenbelt means that the areas being affected are further out than would be otherwise, which leads to the public transport network being under increased and unsustainable pressures. Transport For London (TFL) optimised the transportation network for the London Olympics, with the vision that this would subsequently optimise it for the city for decades to come. All predictions have failed and the transportation network is already filled to the capacity of the Olympics. The new Cross Rail (Elizabeth Line) will at the most optimistic prediction release the pressure for maximum of 2 years at a cost of £14.8 Billion, with some estimating it will actually fill to capacity immediately.

Sticking one’s head in the sand will not make this problem disappear. The cost of building and maintaining the transport system and the cost of lost man-hours in ever longer journeys, by relying on ever larger commuter networks is unsustainable.

The size of the problem in London is substantial. There are currently 69,000 ‘concealed’ families in London, with 17,530 homeless and 49,000 new homes needed each year. In total, London would need 135,530 new homes at the end of the year in order to solve the housing crises. London currently allows 20,000 homes to be built per year. The crisis is scheduled to keep growing by the government. To put these figures in a more understandable form: The average new home in the uk is 76 m2 the smallest in Europe . The Shard, the tallest building in the European Union, is 110,000 m2 in size. 1,274 average homes could fit into the Shard (minus 12% circulation etc). In order to solve the housing need at the end of 2016, we would have to build 106 Shards in London in one year.

So this is the challenge to local residents, councillors, politicians and the RIBA: Where and how will you build the equivalent of 106 Shards in London?

This is a situation that requires foresight, resolve and courage; a Churchill not a Chamberlain.